DOC retrieval using remote sensing and machine learning

Here is a brief summary of a study whose objective was to explore the potential of machine learning in the retrieval of dissolved organic content (DOC) concentrations by remote sensing in the Congo River. The assumption is that machine learning algorithms perform better than the usual simpler algorithms.

Introduction

Rivers play a major and active part in the global carbon cycle. The fluxes from terrestrial ecosystems to freshwater are generated by natural processes but are also very influenced by human action. Therefore, monitoring carbon fluxes in rivers could be a way to quantify the impact that humans have on a basin’s carbon storage and fluxes, through land use and its changes. With global climate change and efforts to reduce the production of greenhouse gases, it is necessary to maintain existing terrestrial stocks as much as possible (Cole et al., 2007).

In addition to particulate organic carbon (POC) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), a significant fraction of the Carbon in water is found as dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and globally, DOC accounts for 20% of organic Carbon (Chen et al., 2020). DOC concentrations vary not only with human processes such as land use, but also by natural processes such as extreme weather events (Cao & Tzortziou, 2021), season, precipitation regimes, and connectivity of the water network (Chen et al., 2020).

Numerous studies have used the relation between organic content (POC or DOC) and physical properties probed by satellites to reconstruct organic matter (for instance Liu et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2020; Cao & Tzortziou, 2021). Nowadays, with the development of Machine Learning (ML) methods, there is a potential in improving the retrieval algorithm working with remote sensing. ML presents different advantages as it can combine a large amount of input features and they do not require a prior knowledge of the nature of the relation between the input features and the predicted variable (Lary et al., 2016). Moreover, they have stronger fitting capabilities than other algorithms (Lary et al., 2016). In the case of the POC for instance, Liu et al. (2021) showed that ML methods performed better than a usual band ratio algorithms.

Data

In situ DOC measurements were provided by the university. For NDA reasons, data and metadata will not be shared. Satellite data from Landsat-7 (USGS Landsat 7 Level 2, Collection 2, Tier 1), LandSat-8 (USGS Landsat 8 Level 2, Collection 2, Tier 1) and Sentinel-2 (Sentinel-2 MSI: MultiSpectral Instrument, Level 2A) were downloaded on Google Earth Engine (Gorelick et al., 2017).

Methodology

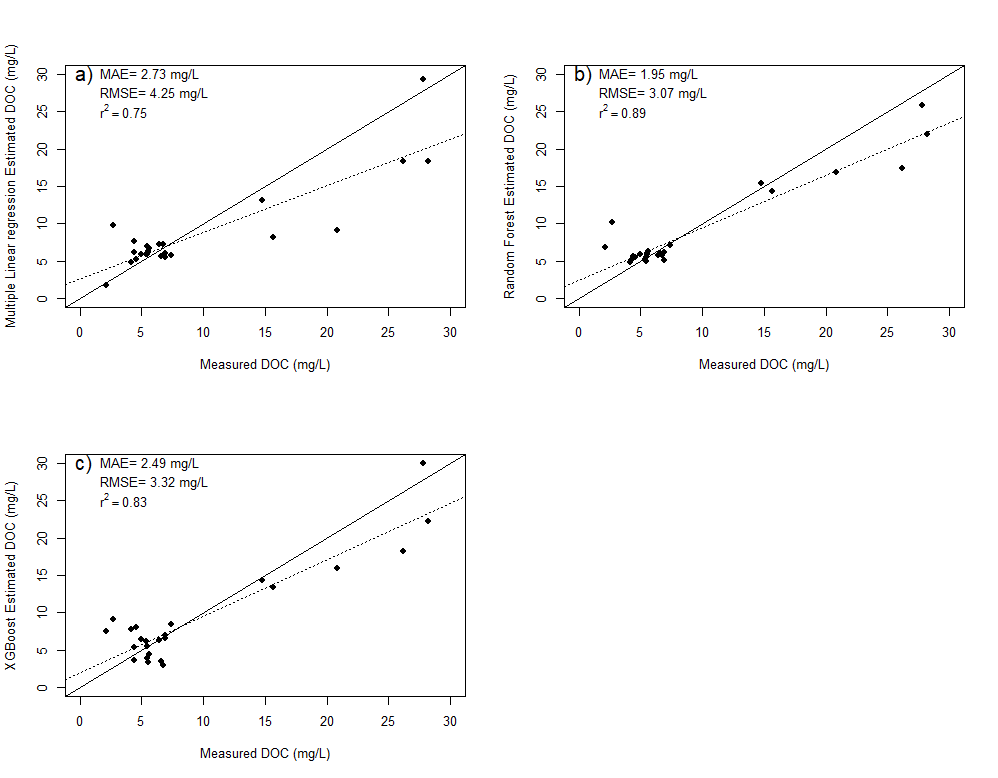

For all retrieval models, the dataset was randomly separated into two subsets for training (85%) and testing (15%). Two different algorithms of machine learning have been used to retrieve DOC: Random Forest (RF; Breiman, 2001) and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost; Chen et Guestrin, 2016). Both are learning algorithms based on the development of decision trees. As input features were used the six bands, Green over Blue (GoB), Green over Red (GoR) and Blue over Red (BoR) ratios (ChunHock et al., 2020) and Normalized Difference Water Index (ndwi), Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (Mndwi) and New Water Index (nwi) (Khalid et al., 2021). The performance of these two algorithms was also compared to a simpler multiple linear regression (MLR) model already used for DOC retrieval and adapted from Cao and Tzortziou (2021):

DOC = exp(a + b*log(BLUE band) + c*log(GREEN band) + d*log(RED band))

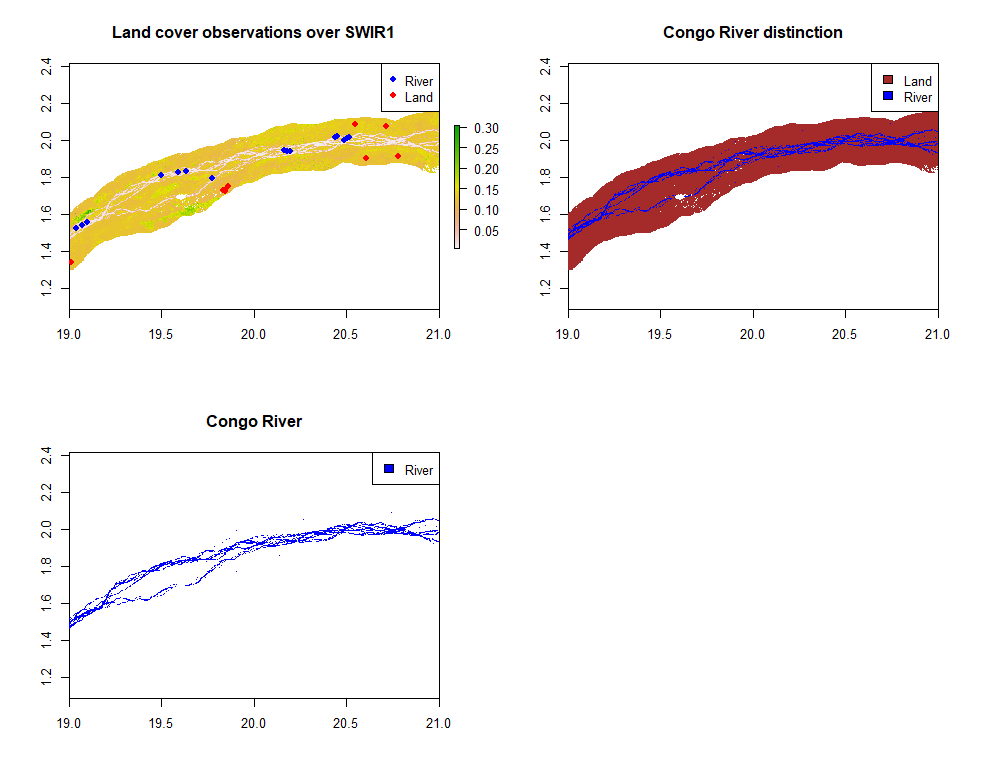

To distinguish the river in satellite images and avoid the meaningless model application on land pixels, a supervised classification has been realised (the algorithm considered the two SWIR bands to be the most useful for this distinction).

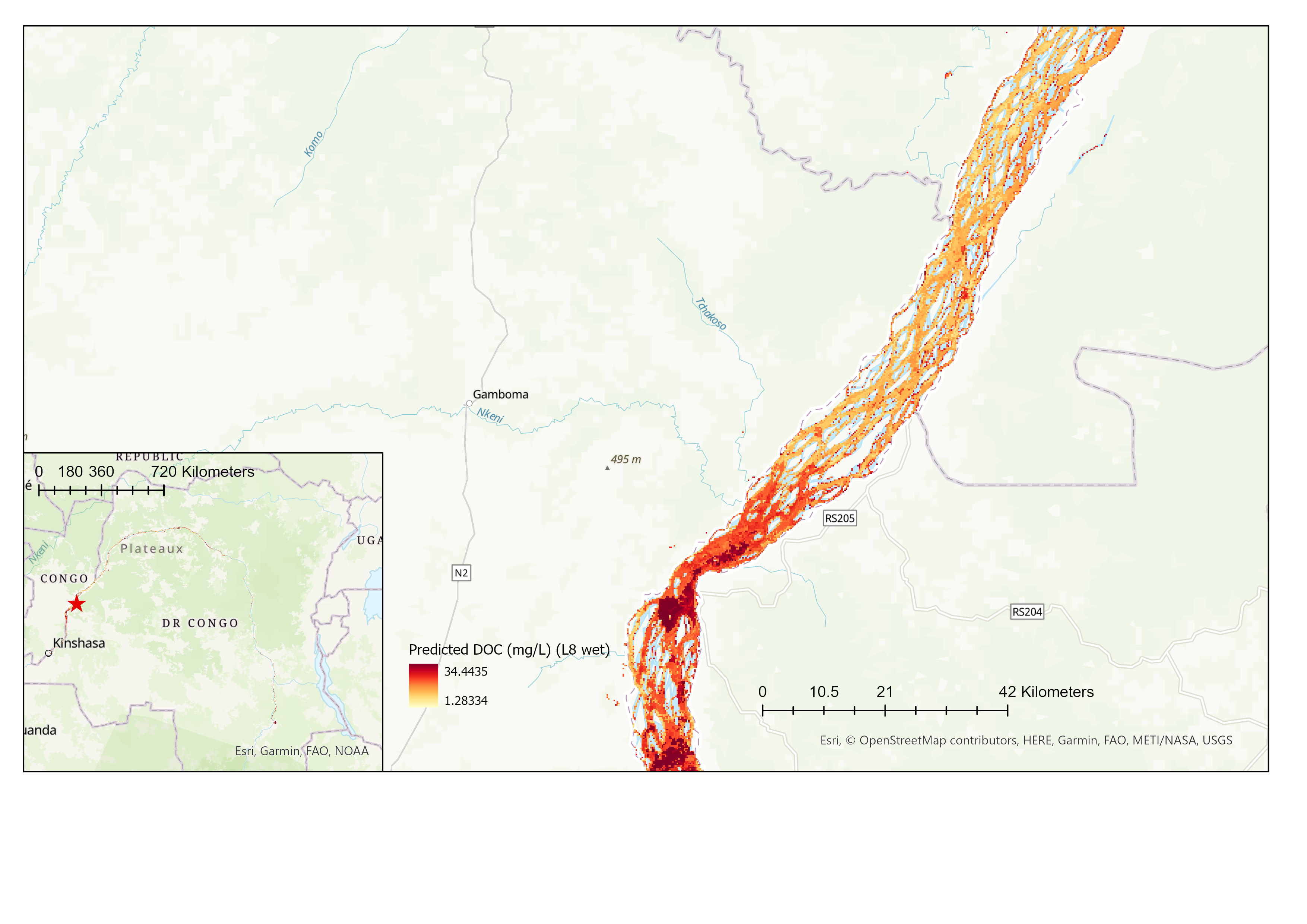

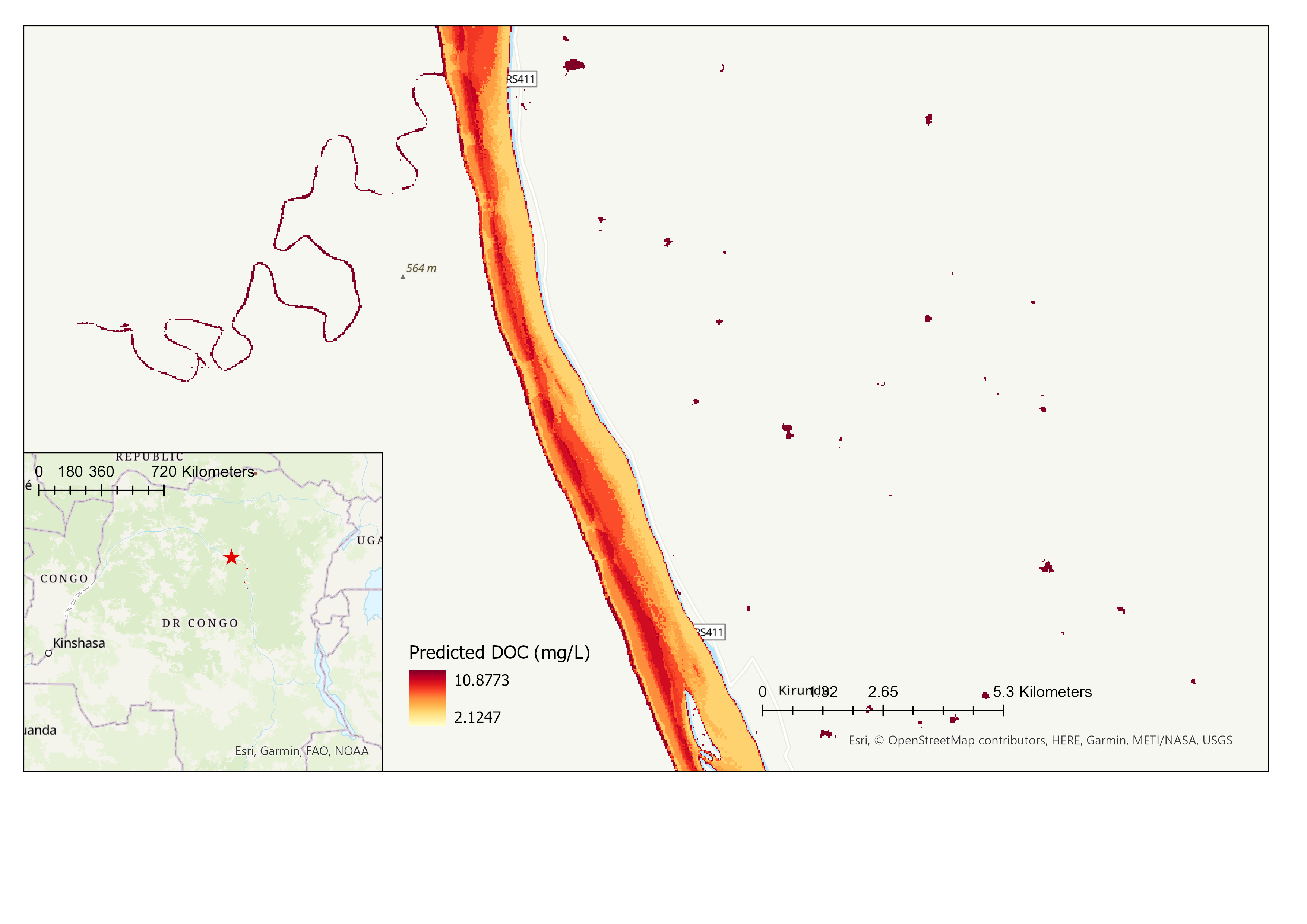

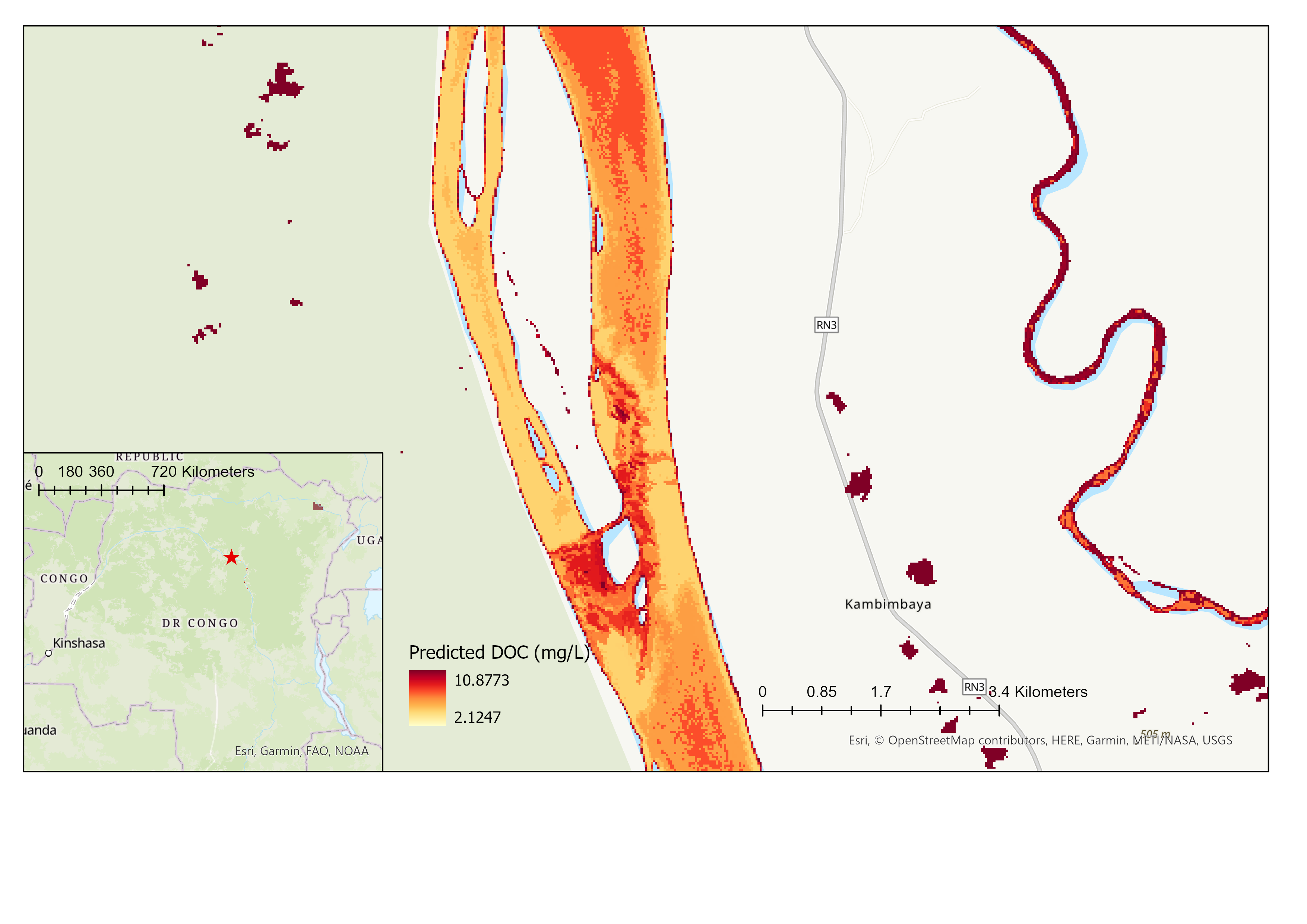

Finally, the DOC retrieval model that presented the best results was applied to different satellite images cropped by the river raster.

Results

Both ML algorithms performed better than the MLR. The RF algorithm performed the best with an RMSE of 3.07 mg/L, MAE of 1.95mg/L. The initial assumption that machine learning algorithms perform better than the usual simpler algorithms is therefore verified. Given its better performance, Random Forest was chosen as the model for the application on satellite images.

Limits

- Few observations to train the models, especially in comparison with the extent of the Congo River which extends over thousands of kilometers, while inland waters are optically complex systems and therefore more challenging than other systems for remote sensing (Palmer, 2015).

- Disproportionately small amount of high DOC values when it is known that ML algorithms do not perform well in the range where they have not been trained.

- Sometimes great time gap between DOC measurements and satellite images while DOC is known to show rapid fluctuations (Cao and Tzortziou,2021).

- Last point amplified by a reduction in useful satellite images due to heavy cloudy conditions in the region.

- etc.

Application to satellite images

References

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine learning, 45(1), 5-32.

- Cao, F., & Tzortziou, M. (2021). Capturing dissolved organic carbon dynamics with Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 in tidally influenced wetland–estuarine systems. Science of the Total Environment, 777, 145910.

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining (pp. 785-794).

- Chen, J., Zhu, W., Tian, Y. Q., & Yu, Q. (2020). Monitoring dissolved organic carbon by combining Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 satellites: Case study in Saginaw River estuary, Lake Huron. Science of the Total Environment, 718, 137374.

- ChunHock, S., Cherukuru, N., Mujahid, A., Martin, P., Sanwlani, N., Warneke, T., ... & Müller, M. (2020). A new remote sensing method to estimate river to ocean DOC flux in peatland dominated Sarawak Coastal regions, Borneo. Remote Sensing, 12(20), 3380.

- Cole, J. J., Prairie, Y. T., Caraco, N. F., McDowell, W. H., Tranvik, L. J., Striegl, R. G., Duarte, C. M., Kortelainen, P., Downing, J. A., Middelburg, J. J., & Melack, J. (2007). Plumbing the Global Carbon Cycle: Integrating Inland Waters into the Terrestrial Carbon Budget. Ecosystems, 10(1), 172–185.

- Gorelick, N., Hancher, M., Dixon, M., Ilyushchenko, S., Thau, D., & Moore, R. (2017). Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment.

- Khalid, H. W., Khalil, R. M. Z., & Qureshi, M. A. (2021). Evaluating spectral indices for water bodies extraction in western Tibetan Plateau. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 24(3), 619-634.

- Lary, D. J., Alavi, A. H., Gandomi, A. H., & Walker, A. L. (2016). Machine learning in geosciences and remote sensing. Geoscience Frontiers, 7(1), 3-10.

- Liu, D., Pan, D., Bai, Y., He, X., Wang, D., Wei, J. A., & Zhang, L. (2015). Remote sensing observation of particulate organic carbon in the Pearl River Estuary. Remote Sensing, 7(7), 8683-8704

- Liu, H., Li, Q., Bai, Y., Yang, C., Wang, J., Zhou, Q., ... & Wu, G. (2021). Improving satellite retrieval of oceanic particulate organic carbon concentrations using machine learning methods. Remote Sensing of Environment, 256, 112316.

- Palmer, S. C., Kutser, T., & Hunter, P. D. (2015). Remote sensing of inland waters: Challenges, progress and future directions. Remote sensing of Environment, 157, 1-8.